The Obama Administration has adopted what it calls “an integrated approach to international criminal justice,” including the International Criminal Court. There are at least six points to this approach, the first three of which are specifically addressed to the ICC.[1]

First, the U.S. will not be seeking U.S. Senate consent to U.S. ratification of the Rome Statute. In January 2010, U.S. Ambassador at Large for War Crimes, Stephen Rapp, publicly stated that no U.S. president was likely to present the Rome Statute to the U.S. Senate for ratification in the “foreseeable future.” Rapp cited fears that U.S. officials would be unfairly prosecuted and the U.S.’s strong national court system as reasons it would be difficult to overcome opposition to ratification. He did not mention the virtual political impossibility in this Congress to obtaining the two-thirds (67) vote in the Senate that would be necessary for ratification.[2] In addition, in March 2011, the U.S. told the U.N. Human Rights Council at the conclusion of its Universal Periodic Review of the U.S. that the U.S. did not accept the recommendations by a number of States that the U.S. ratify the Rome Statute.[3]

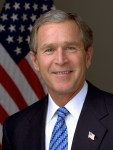

Second, the U.S. Administration will not be seeking statutory changes to U.S. statutes and practices that are hostile to the ICC. This conclusion emerges by implication from the absence of any such proposed legislation and from the same political calculus just mentioned. The Obama Administration, therefore, is living with the laws on the books bolstered by a January 2010 legal opinion from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel that U.S. diplomatic or “informational” support for particular ICC investigations or prosecutions would not violate U.S. law. Other hand-me-downs of past U.S. actions hostile to the ICC are the U.S.’ 102 Bilateral Immunity Agreements or “BIA”s, whereby the other countries agreed not to turn over U.S. nationals to the ICC. The last of these was concluded in 2007. There is no indication that the U.S. will seek to rescind these agreements or to negotiate new ones.[4]

Third, the U.S. instead has been pursuing a policy of positive engagement with the ICC in various ways. Indeed, the U.S. National Security Strategy of May 2010 stated that as a matter of moral and strategic imperative the U.S. was “engaging with State Parties to the Rome Statute on issues of concern and [is] supporting the ICC’s prosecution of those cases that advance U.S. interests and values, consistent with the requirements of U.S. law.”[5]

Foremost for positive engagement is the U.S. participation as an observer at meetings of the ICC’s governing body, the Assembly of States Parties. The U.S. did so in November 2009,[6] March 2010,[7] June 2010[8] and December 2010[9] and has announced its intention to do so at the next meeting in December 2011.

In addition to observing the debates and discussion at these meetings, the U.S. has made positive contributions. The U.S. experience in foreign assistance judicial capacity-building and rule-of-law programs, Ambassador Rapp has said, could help the ICC in its “positive complementarity” efforts, i.e., its efforts to improve national judicial systems. Similarly the U.S. experience in helping victims and reconciling peace and justice demands has been offered to assist the ICC.[10] At the June 2010 Review Conference the U.S. made a written pledge to “renew its commitment to support projects to improve judicial systems around the world.” Such improvements would enable national courts to adjudicate national prosecutions of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide and thereby make ICC involvement unnecessary. The U.S. also pledged at the Review Conference to “reaffirm President Obama’s recognition . . . that we must renew our commitments and strengthen our capabilities to protect and assist civilians caught in the [Lord Resistance Army’s] wake [in Uganda], to receive those that surrender, and to support efforts to bring the LRA leadership to justice.”[11]

The June 2010 meeting was the important Review Conference that adopted an amendment to the Rome Statute with respect to the crime of aggression; this will be discussed in a future post. Immediately after the Review Conference Ambassador Rapp and State Department Legal Advisor Koh said that U.S. participation at the Review Conference “worked to protect our interest, to improve the outcome, and to bring us renewed international goodwill.” All of this reflected U.S. (a) “support for policies of accountability, international criminal justice, and ending impunity,” (b) the U.S. “policy of principled engagement with existing international institutions” and (c) ensuring that lawful uses of military force are not criminalized.[12]

At the December 2010 meeting, Ambassador Rapp emphasized three ways for the world community to help the important work of the ICC. First was protecting witnesses in cases before the ICC and in other venues from physical harm and death and from bribery attempts. Second was enforcing the ICC arrest warrants and bringing those charged to the Court to face prosecution. Third was improving national judicial systems all over the world. In this regard the U.S. endorsed the recent discussion in the Democratic Republic of the Congo about creating a “mixed chamber” of Congolese and foreign judges in its national judiciary with jurisdiction over genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.[13]

The U.S. also is meeting with the ICC’s Prosecutor and other officials to find ways the U.S. can support current prosecutions (consistent with U.S. laws). [14]

As another means of positive engagement with the ICC, the U.S. has continued to support the March 2005 U.N. Security Council referral of the Sudan (Darfur) situation to the ICC, and the U.S. has refused to support any effort to exercise the Council’s authority to suspend any ICC investigations or prosecutions of Sudanese officials for a 12-month period. In January 2009, Susan Rice, the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N., stated that the U.S. supports “the ICC investigation and the prosecution of war crimes in Sudan, and we see no reason for an Article 16 deferral” by the Council. Following the ICC’s issuance of an arrest warrant for Omar al-Bashir, President of Sudan, in March 2009, Ambassador Rice reiterated U.S. support for the Court on Darfur and the requirement of Sudan to cooperate with the ICC. [15]

More recently, the U.S. supported the use of the ICC with respect to Libya. The previously discussed U.N. Security Council Resolution 1970 that referred the Libyan situation to the ICC Prosecutor was prepared by the U.S. and 10 other Council members.[16] During the Council’s discussion of the resolution, U.S. Ambassador Susan Rice stated, “For the first time ever, the Security Council has unanimously referred an egregious human rights situation to the [ICC].”[17]

Three days after the Security Council resolution on Libya, the U.S. Senate unanimously approved a resolution deploring the situation in Libya and Colonel Gadhafi. This resolution also stated that the Senate “welcomes the unanimous vote of the United Nations Security Council on resolution 1970 referring the situation in Libya to the [ICC] . . . .”[18]

Another means of the U.S.’ positive engagement with the ICC is U.S. public diplomacy supporting the Court–publicly support the arrest and prosecution of those accused by the ICC’s Prosecutor and publicly criticizing those who seek to thwart such arrests. In any event, the U.S. has ceased its hostility and harsh rhetoric against the Court.[19]

Fourth, the U.S. will continue to offer financial support and advice to strengthen other national court systems, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo. As previously mentioned, this policy is part of the U.S. positive engagement with the ICC, but it is also part of the broader approach to international criminal justice.[20]

Fifth, the U.S. will continue to support the final work of the ad hoc criminal tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia that were established by the U.N. Security Council with limited time periods of existence. The U.S. will do so by providing funding, by supporting their work diplomatically and politically and by providing evidence and concrete support to the prosecutors and defendants. In particular, the U.S. will work in the Security Council “to create a residual mechanism for the ad hoc tribunals that will safeguard their legacy and ensure against impunity for fugitives still at large” after those tribunals cease to exist.[21]

Ambassador Rapp also has noted that the era of the U.N.’s establishing ad hoc and short-lived tribunals like the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda to address specific problems was over. Only the ICC would be in business for future problems. Therefore, the U.S. needed to be positively engaged with the ICC.[22]

Sixth, the U.S. has said that it must work with countries that exercise universal jurisdiction (like Spain) when there is some relation between the country and the crime. Exactly what that means is not clear. Ambassador Rapp publicly has endorsed the principle of universal jurisdiction as another way to hold human rights violators accountable. On the other hand, as will be discussed in a future post, Spain has at least two pending criminal cases against high-level U.S. officials under Spain’s statute implementing this jurisdictional principle.[23]

In conclusion, we have seen that there is substance to the claim that the Obama Administration has developed “an integrated approach to international criminal justice.” Although I personally believe the U.S. should become a full-fledged member of the ICC, I recognize the current political impossibility of that happening and believe that the U.S. is doing everything that it can to support the important work of the ICC and other courts that are tackling, in the words of Article 1 of the Rome Statute, the “most serious crimes of international concern.”

[1] Koh, The Challenges and Future of International Justice (Oct. 27, 2010), http://www.state.gov/s/l/releases/remarks/150497.htm; U.S. White House, National Security Strategy at 48 (May 2010), http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/national_security_strategy.pdf. See Post: The International Criminal Court: Introduction (April 28, 2011)(overview of structure and operation of ICC).

[2] Belczyk, US war crimes ambassador says US unlikely to join ICC in ‘forseeable future,’ Jurist (Jan. 28, 2010), http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/paperchase/2010/01/us-war-crimes-ambassador-says-us.php.

[3] On January 4, 2011, the Human Rights Council’s Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review of the U.S. issued its final report on the UPR of the U.S. It set forth all the recommendations of the States without endorsement by the Working Group as a whole. This report again included the specific recommendations for the U.S. to ratify the Rome Statute. (U.N. Human Rights Council, Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review–United States of America ¶¶ 92.1, 92.2, 92.16, 92.25, 92.28, 92.36 (Jan. 8, 2011), http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G11/100/69/PDF/G1110069.pdf?OpenElement.) On March 8, 2011, the U.S. submitted its response to this final report. Among other things, the U.S. specifically rejected the recommendations that the U.S. ratify the Rome Statute. (U.N. Human Rights Council, Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review–United States of America: Addendum: Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review ¶¶ 29, 30 (March 8, 2011), http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G11/116/28/PDF/G1111628.pdf?OpenElement.) Nevertheless, the Council adopted the Working Group report in March 2011. (U.N. Human Rights Council, HR Council Media: Human Rights Council concludes sixteenth session (March 25, 2011).)

[4] AMICC, The Obama’s Administration’s Evolving Policy Toward the International Criminal Court (March 4, 2011), http://www.amicc.org/docs/ObamaPolicy.pdf; Congressional Research Service, International Criminal Court Cases in Africa: Status and Policy Issues (March 7, 2011), http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/158489.pdf. See Post: The International Criminal Court and the G. W. Bush Administration (May 12, 2011).

[5] U.S. White House, National Security Strategy at 48 (May 2010), http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/national_security_strategy.pdf.

[6] AMICC, Report on the Eighth Session of the Assembly of States Parties, The Hague, November 2009 http://www.amicc.org/docs/ASP8.pdf; Stephen J. Rapp, Speech to Assembly of States Parties (Nov. 19, 2009), http://www.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/asp_docs/ASP8/Statements/ICC-ASP-ASP8-GenDeba-USA-ENG.pdf.

[7] AMICC, Report on the Resumed Eighth Session of the Assembly of States Parties, New York, March 2010 (March 31, 2010), http://www.amicc.org/docs/ASP8r.pdf; U.S. Dep’t of State, Statement by Stephen J. Rapp . . . at the Session of the Assembly of States Parties of the [ICC], (March 23, 2010), http://usun.state.gov/briefing/statements/2010/138999.htm; U.S. Dep’t of State, Statement by Harold Honju Koh . . . at the . . . Session of the Assembly of States Parties of the [ICC], (March 23, 2010), http://usun.state.gov/briefing/statements/2010/139000.htm.

[8] AMICC, Report on the Review Conference of the International Criminal Court (June 25, 2010), http://www2.icc-cpi.int/Menus/ICC/Home; http://www.amicc.org.

[9] U.S. Mission to the U.N., Statement of the U.S.A. by Ambassador Stephen Rapp to the Assembly of States Parties, (Dec. 7, 2010), http://www.amicc.org/docs/ASP_Rapp_Statement_12072010.pdf; AMICC, Report on the Ninth Session of the Assembly of States Parties, December 2010, http://www.amicc.org/docs/ASP9.pdf.

[10] AMICC, Report on the Resumed Eighth Session of the Assembly of States Parties, New York, March 2010 (March 31, 2010), http://www.amicc.org/docs/ASP8r.pdf; U.S. Dep’t of State, Statement by Stephen J. Rapp . . . at the Session of the Assembly of States Parties of the [ICC], (March 23, 2010), http://usun.state.gov/briefing/statements/2010/138999.htm; U.S. Dep’t of State, Statement by Harold Honju Koh . . . at the . . . Session of the Assembly of States Parties of the [ICC], (March 23, 2010), http://usun.state.gov/briefing/statements/2010/139000.htm.

[11] AMICC, Report on the Review Conference of the International Criminal Court (June 25, 2010), http://www2.icc-cpi.int/Menus/ICC/Home; http://www.amicc.org. The U.S. pledge about the LRA was prompted by the enactment of the Lord’s Resistance Army Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act of 2009. (Wikisource, Lord’s Resistance Army Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act of 2009, http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/ Lord’s_Resistance_Army_Disarmament_and_Northern_Uganda_Recovery_Act_of_2009; U.S. White House, Statement by the President on the Signing of the Lord’s ResistanceArmy Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act of 2009 (May 24, 2010), http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/statement-president-signing-

Lords-resistance-army-disarmament-and-northern-uganda-r.

[12] U.S. Dep’t of State, U.S. Engagement with The International Criminal Court and The Outcome of The Recently Concluded Review Conference (June 15, 2010), http://www.state.gov/s/wci/us_releases/remarks/143178.htm.

[13] Id. The ICC currently is investigating and prosecuting cases from the DRC. See Post: The International Criminal Court: Investigations and Prosecutions (April 28, 2011).

[14] Id.

[15] E.g., Statement by President Obama on the Promulgation of Kenya’s New Constitution (Aug. 27,2010), http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2010/08/27/statement-president-obama-promulgation-kenyas-new-constitution(“I am disappointed that Kenya hosted Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in defiance of International Criminal Court arrest warrants for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. The Government of Kenya has committed itself to full cooperation with the ICC, and we consider it important that Kenya honor its commitments to the ICC and to international justice, along with all nations that share those responsibilities”); U.N. Security Council, Press Release: Briefing Security Council on Sudan, United Nations, African Union Officials Tout Unified Strategy, Linking Peace in Darfur to Southern Sudan Referendum (June 14, 2010), (U.S. Ambassador Rice told Security Council that there was a need “to bring to justice all those responsible for crimes in Darfur, calling on Sudan to cooperate with the [ICC] and expressing deep concern at the Court’s Pretrial Chamber judges recent decision to refer the issue of Sudan’s non-cooperation to the Council”).

[16] U.N. Security Council 6491st meeting (Feb. 26, 2011). Other Council members (Bosnia & Herzogiva, Colombia, France, Germany, Libya and the U.K.) specifically commended the reference to the ICC. The other four Council members who did not join in drafting the resolution were Brazil, China, India and the Russian Federation. In the meeting, the Indian representative noted that “only” 114 of the 192 U.N. Members were parties to the Rome Statute and that five of the 15 Council members, including three permanent members (China, Russia and U.S.), were not such parties. He went on to emphasize the importance of Article 6 of the resolution’s exempting from ICC jurisdiction nationals of States like India that were not parties to the Rome Statute and its preamble’s stating that the Statute’s Article 16 allowed the Council to postpone any investigation or prosecution for 12 months. (Id.) The Brazilian representative was serving as President of the Council and, therefore, may not have participated in drafting the resolution, but she noted that Brazil was a “long-standing supporter of the integrity and universality of the Rome Statute” and expressed Brazil’s “strong reservation” about Article 6’s exemption of nationals of non-States Parties. (Id.) This suggests that the inclusion of Article 6 was the price of obtaining “yes” votes for the resolution from India, China and the Russian Federation. See Post: The International Criminal Court: Investigations and Prosecutions (April 28, 2011).

[17] U.N. Security Council 6491st meeting (Feb. 26, 2011).

[18] ___Cong. Record S1068-69 (March 1, 2011) (S. Res. 85).

[19] Koh, The Challenges and Future of International Justice (Oct. 27, 2010), http://www.state.gov/s/l/releases/remarks/150497.htm.

[20] ICC, Review Conference of the Rome Statute: Pledges (July 15, 2010), http://www2.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/asp_docs/RC2010/RC-9-ENG-FRA-SPA.pdf.

[21] Belczyk, US war crimes ambassador says US unlikely to join ICC in ‘forseeable future,’ Jurist (Jan. 28, 2010), http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/paperchase/2010/01/us-war-crimes-ambassador-says-us.php.

[22] Id. With the existence of the ICC, there is no need to create future ad hoc tribunals. This fact also avoids the administrative problems ad hoc tribunals face when they near the end of their lives and professional and other staff leave to pursue other opportunities with greater future prospects. (See Amann, Prosecutorial Parlance (9/12/10), http://intlawgrrls.blogspot.com (comments by officials of ICTY and ICTR).)

[23] Belczyk, US war crimes ambassador says US unlikely to join ICC in ‘forseeable future,’ Jurist (Jan. 28, 2010), http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/paperchase/2010/01/us-war-crimes-ambassador-says-us.php.